by Zachary Marschall, PhD

There is no faster – or more amusing – way to make a campus radical lose his composure than to fuss about the importance of cultural literacy.

The term “cultural literacy,” made popular by the controversial scholar E.D. Hirsch, describes a person’s capacity to comprehend cultural references and use that knowledge in conversation with others.

For example, many Americans understand references to the British novel Frankenstein in this nation’s popular culture, whether in television shows, daily conversation, or Halloween costumes. That ability to interpret references to events, names, or trending hashtags is cultural literacy.

People acquire cultural literacy through education and socialization, and then utilize it in their social and professional networks to participate fully in those circles.

The American education system’s traditional emphasis on classic Western texts – what the celebrated professor Harold Bloom dubs The Western Canon – sets leftist academics off on incoherent rants about cultural literacy’s purportedly discriminatory nature, none of which seem to land on a logical reason for why knowing a Shakespearean sonnet or the capital of Florida is harmful to minority students.

Hirsch and Bloom are two key players in the tradition of conservative scholars publishing important books on the crisis in American education.

Another Bloom, the University of Chicago professor Allan Bloom, wrote The Closing of the American Mind in 1987, which critiques the multigenerational downfall of liberal education on college campuses and the rise of intolerant ideological critique in its place.

The American university has been in steady decline for decades due to the same set of reasons – namely an institutionalized pursuit of closeminded activism over curiosity-driven reason. But the pace at which leftist activists expect change for myriad causes appears to have only increased with time since Closing of the American Mind first debuted.

That paradox makes writing a timely book on higher education’s prolonged decay all-the-more a moving target, as this year’s paperback edition of The Breakdown of Higher Education demonstrates.

John M. Ellis, a professor emeritus of German Literature at the University of California, Santa Cruz, notes in his preface that the book’s manuscript was finalized two years before the paperback’s release in August 2021. And that time gap is telling.

The Breakdown, which originally came out in 2020, details numerous recent examples of anti-progressive females facing vocal and physical opposition to their campus speaking engagements. Ellis’ repeated mentions of Christina Hoff Sommers, senior fellow at American Enterprise Institute, and City Journal editor Heather Mac Donald, expose the mistreatment of these women by radicals regardless of gender.

But these anecdotes – well-known to those that follow campus news – do not account for the systematic erasure of women across America.

Campus Reform reports regularly on that erasure.

Academic leftists now call females “people with uteruses” and dub expectant mothers “birthing people.”

Radical feminism may have once been the enemy of tradition, but now feminism – which relies on the premise that women are unique to men – is at odds with the transgender movement’s agenda to neutralize all distinctions for “inclusivity.”

But the book’s omission on the divide between feminism and transgenderism is an indictment of the woke left’s frenzied social justice warlording on campus, not of Ellis’ exhaustive explanation for the institution’s rot. In fact, the author’s frequent references to campus administrators caving to heckler’s vetoes reveal the strength of The Breakdown.

Ellis makes clear that the story of higher education’s failings is one about people, not the institution of the university itself.

That distinction comes through most clearly in the chapter “Graduates Who Know Little and Can’t Think.” Here, Ellis demonstrates that every critique of higher education that blames the institution, rather than its people, misses the mark.

The emeritus professor eloquently informs readers that higher education’s current predicament is the result of an inflection point in American history that aligns with the Vietnam War.

Around the same time that Vietnam radicalized the nation’s left, post-World War II legislation that made college widely accessible to Americans dramatically increased the need for additional university campuses and teaching positions.

The nation’s academic labor market was artificially expanded by the federal government at a time when the increased hiring made radical takeover of universities an inevitable numbers game.

These events set in motion the current feedback loop in which graduate students are trained in Marxist or Marxist-inspired ideologies and go to fill the vacancies once held by their mentors. Those former students then become the professors who are intent on indoctrinating the upcoming graduate cohorts.

That cycle then repeats itself with each new generation, only solidifying the echo chamber further into what are now insufferable university Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity committees.

Unfortunately, Ellis’ diagnosis is not partisan. It would be somewhat comforting if his narrative could be explained away as a conservative crank’s misgivings.

No. Ellis’ account aligns with other books in its genre across the political spectrum because it confronts the role people have played in higher education’s dissolution.

He reveals that by condemning cultural literacy, radical activists have devastated what made American colleges wonderous institutions.

Ellis writes, “Not so very long ago, large populations of recent immigrants–Italians, Irish, Jews–began life in America as the downtrodden poor, but access to first-rate public education enabled them to become fully integrated into American society and to enjoy all of its blessings.”

The history Ellis condenses in this passage is told through memoir in the late Morris Dickstein’s 2015 book Why Not Say What Happened: A Sentimental Education.

Dickstein, who was an English professor at the City University of New York, belonged to that first generation of American Jews who enjoyed a respectable level of equality and fair treatment in academia and society.

Describing relationships with his mentors and the relative ease of securing a teaching position after submitting his dissertation, Dickstein shows how accumulation of cultural literary and access to the Western Canon were key to minorities’ participation and acceptance in academia and wider American culture.

Arguably, Asian Americans now occupy that same precarious social position that Jews held nearly a century ago in the United States.

In the early 20th century, some American Jews experienced privilege, but the minority as a whole was subjected to widespread discrimination, which included derogatory cultural stereotypes and university quotas that left them disadvantaged.

Today, Asian Americans face similar discrimination in higher education, particularly admissions, due to stereotypes about the ethnic group’s intelligence and affluence.

Education is the key to full participation in society, which explains why the acquirement of cultural literacy helped American Jews overcome so much discrimination, and why so many Asian American immigrant families find success here.

Removing rigor from academia robs every American of similar opportunities.

For that reason, the tyranny of lower expectations is a real evil lurking in this country. In the name of equity, academic leftists have done away with honors tracks in high school and academic rigor in college, to name a few examples, because they resent the achievement of others.

Those leftist policies that expect less from students are an assault on Americans that understand the value of a liberal education.

As Ellis contends, America is a nation of immigrants that have thrived by pursuing excellence in and outside of the classroom. Embracing rigorous expectations is a part of the immigrant experience that truly transcends cultural boundaries.

When radicals in universities and governments attempt to legislate away those values, they are delegitimizing the stories of countless minority groups in this country. That is neither equality nor equity; it is a vindictive expression of power.

Ellis is at his best when he makes the reader confront the people responsible for higher education’s current crisis and the people who suffer from its decline:

For minorities, the transformation of the curriculum by radical activists has been nothing short of catastrophic. When Jesse Jackson marched with students at Stanford University chanting ‘Hey Hey, Ho Ho, Wetern Civ has got to go,’ he was helping to destroy the chance of upward mobility for the groups that he claimed to be leading and championing. He was putting a rigorous, well-rounded education in the great classic writers and thinkers out of their reach just when they needed it most. And the resulting dumbing down of the education of high school teachers guaranteed that black students would arrive at college with a handicap every bit as great as it has ever been. Denying black students a mastery of the way that modernity came about was denying them a fair chance of advancement. When you see high black unemployment, especially young black male unemployment, blame campus radicals.

The plight of the American university is about people, both the perpetrators and the victims.

The institution was wonderous not because every college was wonderful, or discrimination never existed; universities opened minds and created opportunities by cultivating curiosity and knowledge.

A series of arbitrary events gave one politically homogenous group of people the power to dictate what American higher education would do to its student bodies – both on campus and later in life.

The “American Mind” is already closed and is now being weakened by leftist indoctrination and power on campus.

Contrary to leftists’ false narratives on diversity and intersectionality, radical administrators and professors are not helping students become better people. They are what’s making the college experience monstrous.

Those who know what a traditional rigorous liberal education can provide to the human mind and soul will never concede radical leftists’ lies.

– – –

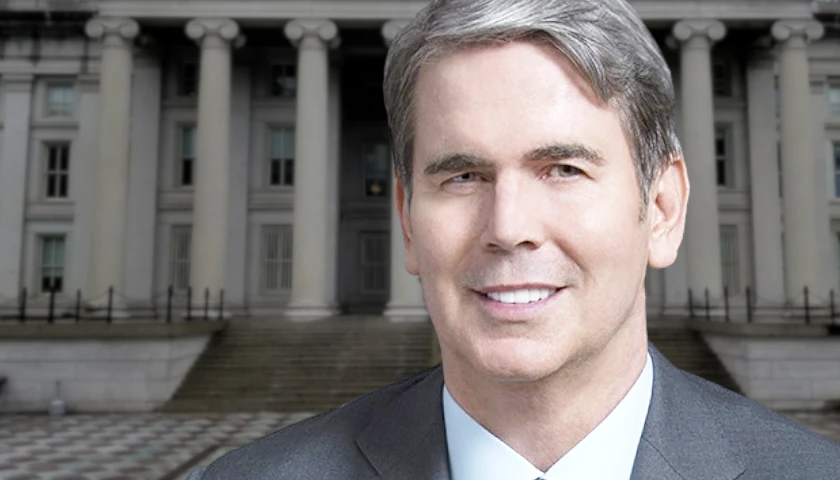

Zachary Marschall is the Managing Editor for Campus Reform. He received a PhD from George Mason University and is an Adjunct Assistant Professor at the University of Kentucky. “Academically Speaking,” his series for Campus Reform, reveals how radical ideas originating in academia impact Americans’ daily lives.

Zachary received his master’s degree from the Newhouse School at Syracuse University and helped launch the peer-reviewed journal Arts & International Affairs in 2015 as the publication’s inaugural Managing Editor. He is also a former student member of the National Association of Scholars and holds a BA from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts.

Photo “Students on campus” by University System of Georgia.

“Academically Speaking” is a series by Campus Reform Managing Editor Zachary Marschall that, drawing on his firsthand experience working with other scholars across the globe, to reveal how radical ideas originating in academia impact Americans’ daily lives. Marschall holds a PhD in Cultural Studies and is an adjunct professor at the University of Kentucky. His research investigates the intersections of democratic political systems, free market economies, and technological innovation in the production of national and cultural identities, as well as the exchange of cultural goods, services, and practices.